On February 12, 1984, Jens Weißflog’s career really took off. After winning Olympic gold, numerous other triumphs followed, making the “Flea from Fichtelberg” Germany’s most successful ski jumper to date.

Jens Weißflog waited for the starting signal on February 12, 1984, to zoom down the normal hill in Sarajevo. Perfect conditions prevailed at the Olympic Winter Games, which were held for the first time in a socialist country in 1984.

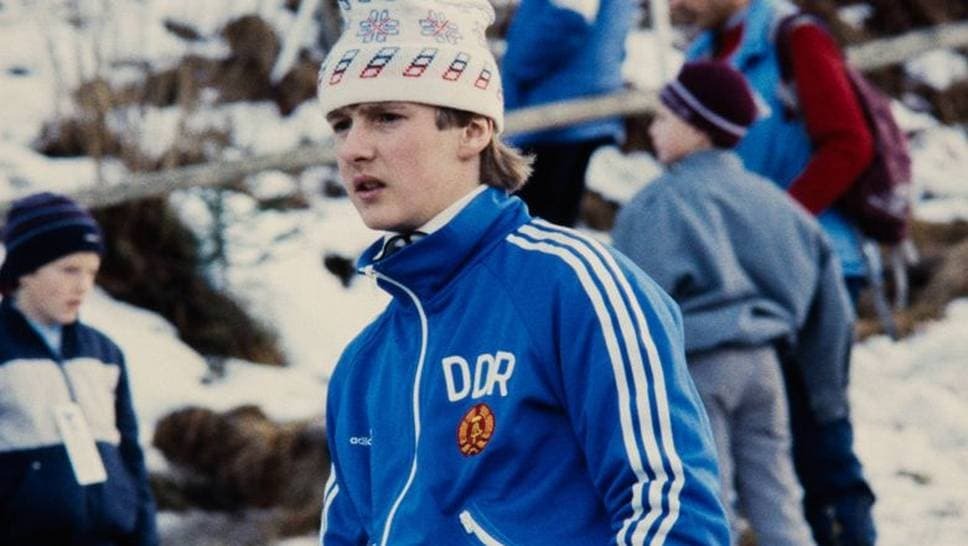

When Weißflog, in a blue suit with number 50, saw the waved flag from the official, he set off and flew 87 meters from the normal hill. It meant: first place for “Jens Weißflog, GDR”.

Jens Weißflog wins his first Olympic gold in Sarajevo

“I can still remember that moment very well, even with some distance. I went to Sarajevo as a favorite back then and already thought I would win gold. But as a 19-year-old, you don’t really perceive what happened back then,” Weißflog recalled in an interview with SPORT1 .

At first, it didn’t look like a triumph for the German: “On that day, there was a duel between Matti Nykänen and me. Matti led after the first round, and I turned it around in the second attempt – that was the fulfillment of a lifelong dream. I always compare this victory with the one in Lillehammer in 1994, but in Sarajevo, it was my first gold medal.”

Weißflog and the self-built ski jump

Although he won two Olympic golds in Lillehammer in 1994 (individual and team victory from the large hill) with a different style and a different flag (that of the Federal Republic of Germany), he perceived his success in 1984 differently. “The emotions were completely mixed up in that moment,” he remembered, “between cheers and tears, it was no longer controllable.”

Weißflog also celebrated victories in all other important competitions. “Ski jumping went from top to bottom in the West and in the East. And whoever jumped the farthest and most beautifully won. That didn’t change due to political systems. And it was clear to me that I would be judged by that and not by other things,” Weißflog, born in the Erzgebirge, once said.

Already at a young age, he earned the nickname “Floh” (flea) because Weißflog was of small stature and could jump like one. In Pöhla, he first tried jumps from a self-built ski jump.

Through his victory in 1984, Weißflog, then 20 years old, became famous overnight. The media in the former GDR saw him as a “real man,” who was simultaneously shy, kind, and modest.

Although Weißflog traveled to competitions all over the world, he had little contact with athletes from the West. He never thought of fleeing the GDR. “Nevertheless, it was always completely normal for me to come back again and again. I couldn’t have imagined staying in the West either. My parents and siblings were here; that’s simply what you associate with home,” Weißflog recounted.

Successful even after reunification

When the turn (reunification) finally came, Jens Weißflog was also thrown off track. In ski jumping, there was a switch from the parallel to the V-style, where the skis are opened like a “V” during flight.

The transition was not easy for Weißflog either. In an interview with SPORT1 , he explained how he still managed the change: “It took longer for me too than I initially thought. But for me, it was immediately clear: the switch to the V-style does not mean the end of my career. It was really only a matter of time until I got it right. However, it took a year until I was back at the top of the world.”

Jens Weißflog on the occasion of the recording of the MDR – talk show Riverboat in February 2024

The German also took inspiration from other jumpers: “I took a jumper from Austria as a role model back then, Ernst Vettori. He was the first Olympic champion in the V-style in 1992. I thought to myself: If he, as an old geezer, can do that, I’ll certainly be able to do it too.”

While this change meant the end of some ski jumpers’ careers, Weißflog managed to adapt. Nevertheless, he didn’t know how things would continue for him, as he had lost his job as an electrician. But here too, he was lucky as he found a sponsor and was able to continue with the sport.

“With the turn, a lot broke away, to the extent that many no longer had financial security and had to take care of themselves. Will I get a sponsor who will support me enough to continue practicing the sport? Those were very exciting times, which were incredibly instructive,” said Weißflog.

Two years after the double triumph of 1994, Weißflog put his skis aside and became not a coach, but a hotelier. From one day to the next, he had to deal with notary contracts, taxes, and occupancy plans.

“These were formulations where I always thought: Can’t you write that a little simpler? But it helped to delve into things and gain a perspective on matters that you didn’t have before. That was a challenge. I wasn’t necessarily looking for it, but I enjoyed it from the start,” revealed Weißflog, in whose hotel in Oberwiesenthal numerous photos still commemorate his fantastic career – including 1984.